The Jatiya Nagorik Party or the National Citizens Party (NCP) emerging from the Students Against Discrimination (SAD) movement, appears to be positioning itself as a significant player in Bangladesh’s political landscape following the dramatic events of the July 2024 protests and the subsequent fall of the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League government.

The July protest in Bangladesh was launched by the leaders of several student organizations and political parties from the beginning. Their names are Ganatantrik Chhatra Shakti, Chhatra Federation, Islami Chhatra Shibir, Chhatra Odhikar Parishad, Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dol, and a faction of Bangladesh Students Union at Dhaka University from July 1, 2024. Their main demand was to revoke the freedom fighters quota, reinstated on June 5 of the same year in a High Court order after six years.

On July 4, the students formed a platform named Students Against Discrimination or Boishomyobirodhi Chhatra Andolon.

By July 6, all anti-Awami League parties of the opposition alliance, which was formed in 2022, lent support to the anti-quota movement.

The student coordinators and politicians sat together many times during the movement. They were also in touch with the US embassy in Dhaka, civil society leaders including Nobel laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus, Badiul Alam Majumder, Prof Ali Riaz, Prof Asif Nazrul, Syeda Rizwana Hasan, expatriate journalists Tasneem Khalil, Zulkarnain Saer Sami, David Bergman, Mushfiqul Fazal Ansary, and social media influencers Pinaki Bhattacharjee, Elias Hossain, Dr Kanak Sarwer, Khaled Mohiuddin for logistics, planning and financing.

Islamist groups like Qawmi madrasa-based Hefazat-e-Islam, and banned militant groups like JMB, AQIS, ISIS, HuJI-B, and Jama’atul Ansar Fil Hindal Sharqiya, ARSA and Hizb ut-Tahrir were active on the streets to fight police and Awami League supporters. They were involved in killing police, Awami League supporters and minorities as well as looting, arson and vandalism.

In early March, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Volker Türk revealed that during the July protests, he threatened the Bangladesh Army with enforcing restrictions on its peacekeeping participation if they got involved in suppressing the movement.

“The big hope for them was actually our voice, was my voice, and was also what we were able to do and we put the spotlight on the situation. And we actually gave the warning to the army that if they get involved, it means that they may not be allowed to be a troop-contributing country anymore,” he said. “As a result, we saw changes.”

It can be assumed that the communication took place between July 18 and 23. Volker Türk’s warning came at a time when the government formed a judicial inquiry commission to investigate the deaths from July 16-21, and Muhammad Yunus issued a statement asking the world to stand up against police excesses in an open letter from France on July 22.

Earlier, opposition leaders and like-minded civil society leaders who are linked to the US Embassy took to the streets after the State Department spread a rumour of two deaths during protests on July 15.

The most fierce attacks on law enforcement, Awami League supporters and state properties amid blockades in the first five days of August triggered more deaths on both sides as the army remained inactive, which is tantamount to a soft coup.

Since August, the conspirators and the street fighters of the camouflaged government ouster movement have already revealed their roles in the riots to establish supremacy in the government and the King’s party, with mobocracy being the interim government’s main strength.

A similar UN intervention emerged before the 1/11 changeover of January 11, 2007, when the then-army chief forced the president to step down as the chief adviser, declare emergency and approve a US-prescribed and pro-Islamist civil society-led interim government, which aimed at weakening the Awami League and the BNP, but miserably failed in reform initiatives and anti-corruption drives.

The army held a meeting called “Officers Address” on August 3 last year. There, it reportedly agreed not to fire on citizens. A press release by the Inter Services Public Relations had said, “The Bangladesh Army will always stand by the people in their interests and the state’s needs.”

On the night of August 4, the army chief assured the Prime Minister and Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal of taking adequate measures to prevent the mob from entering Dhaka. But the army was inactive, and instead, some retired or expelled army members were seen with the anti-government protesters with arms, with the police force retreating in fear of mob violence.

After the army relocated Sheikh Hasina to India on August 5, the student coordinators and their patrons chose Yunus for the post of chief adviser. They later formed the Jatiya Nagorik Committee with seniors and later formed the Jatiya Nagorik Party. Meanwhile, they abolished the convening committee of Ganatantrik Chhatra Shakti, which was formed in October 2023 by some leaders of SAD.

The top leaders of SAD are now leading the Jatiya Nagorik Party and are regarded as the King’s party because they enjoy privileges from the Yunus-led interim government.

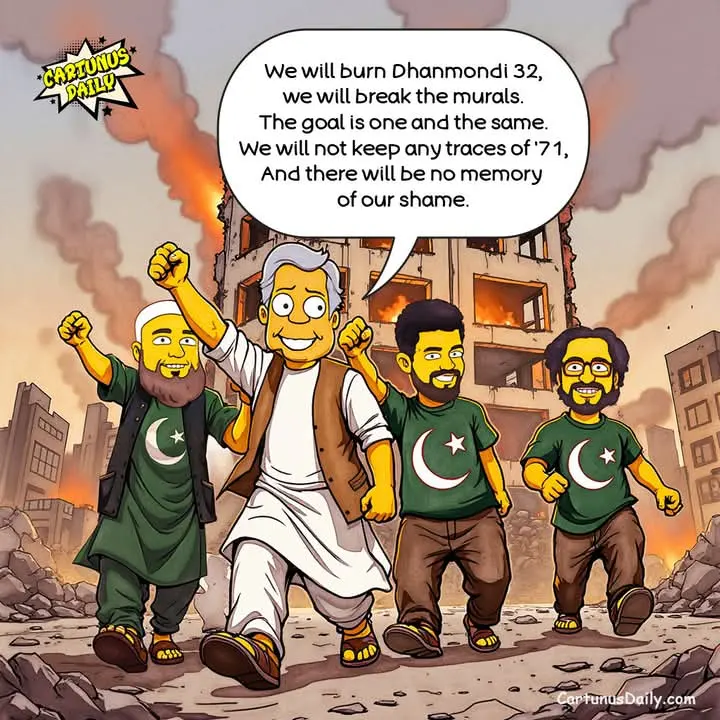

The party aims to ban the Awami League and suppress any party or individual supporting the Awami League’s philosophy, spread hatred against India, and support the pro-Pakistani normalization campaign, revoke secularism, and abuse power to ensure the highest vote in the next elections, as alleged by politicians and observers.

Its political philosophy and potential scope can be analyzed from several angles:

Political Philosophy

Anti-Awami League Stance: The party’s core identity seems rooted in opposition to the Awami League, with an explicit aim to ban it and suppress its supporters. This suggests a retaliatory and exclusionary approach, prioritizing the elimination of a specific ideological rival over broader national reconciliation or unity.

Shift from Secularism: Allegations of revoking secularism indicate a possible tilt toward a more religiously influenced governance model, potentially aligning with Islamist factions that were active during the protests. This could appeal to conservative and religious segments of society but risks alienating secularists and minorities who have historically supported the Awami League’s secular framework.

Anti-India and Pro-Pakistan Sentiment: The party’s alleged anti-India stance and support for normalizing ties with Pakistan mark a significant geopolitical shift. This could resonate with nationalist or anti-establishment voters frustrated with India’s perceived influence in Bangladeshi politics but might complicate foreign relations, especially given Bangladesh’s economic and strategic ties with India.

Authoritarian Tendencies: Accusations of abusing power to secure electoral dominance suggest the party may adopt undemocratic tactics, a pattern not uncommon in post-revolutionary political movements. This could undermine its legitimacy if it fails to deliver on democratic promises made during the anti-quota movement.

Populist Roots: Stemming from a student-led movement against the freedom fighters’ quota, the party retains a populist appeal, potentially drawing support from youth and anti-establishment groups. However, transitioning from a protest movement to a governing entity often dilutes such idealism, especially if privileges from the Yunus-led interim government taint its grassroots image.

Scope in the Political Arena

Current Advantages: The party enjoys significant leverage as the so-called “King’s party” under the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus. This backing, combined with the momentum from the successful ouster of Hasina, gives it a head start in organizing and mobilizing support. The involvement of high-profile civil society figures and international connections (e.g., the US embassy, expatriate journalists) could further bolster its resources and visibility.

Opposition Weakness: With the Awami League in disarray after Hasina’s exit, the opposition landscape is fragmented. The Jatiya Nagorik Party could exploit this vacuum, especially if it effectively consolidates the anti-Awami League coalition, including student groups and Islamist factions.

Challenges from Islamist Allies: The involvement of groups like Hefazat-e-Islam and banned militant outfits (JMB, AQIS, ISIS, etc.) during the protests is a double-edged sword. While these groups amplified the movement’s street power, their extremist ideologies and violent actions (e.g., targeting minorities, police, and Awami League supporters) could alienate moderate voters and invite international scrutiny, limiting the party’s broader appeal.

Electoral Viability: The party’s alleged goal of securing the “highest vote” through power abuse suggests it may prioritize short-term gains over sustainable legitimacy. Bangladesh’s history of electoral controversies and public backlash against rigging could turn this strategy into a liability if not executed with finesse or if it faces resistance from a resurgent civil society.

Geopolitical Risks: The anti-India, pro-Pakistan pivot could isolate Bangladesh regionally, especially if India responds with economic or diplomatic pressure. This stance might also attract covert support from Pakistan or other actors but risks destabilizing Bangladesh’s economy, which relies heavily on trade with India.

Public Perception: The transition from a student-led anti-discrimination platform to a privileged political entity risks eroding its moral credibility. If the public perceives it as a tool of the interim government or a vehicle for personal ambition (e.g., the “top leaders” of SAD), its populist base could fracture.

Grim Future

The Jatiya Nagorik Party has the potential to become a dominant force in Bangladesh’s political arena in the short term, leveraging its protest origins, interim government support, and the Awami League’s collapse. However, its political philosophy—marked by exclusionism, a possible religious shift, and geopolitical realignment—carries significant risks. Its success will depend on how it balances its revolutionary rhetoric with governance, manages its Islamist allies, and navigates public expectations in a polarized society. If it overplays its authoritarian tendencies or fails to deliver on economic and social fronts, it could face resistance from both domestic opponents and international stakeholders, limiting its long-term importance. Conversely, if it moderates its stance and builds a broader coalition, it could reshape Bangladesh’s political future. The next elections will be a critical test of its viability.

Leave a Reply