Two recent news reports on Cox’s Bazar-Matarbari Road—the country’s most expensive—by the daily Prothom Alo and The Daily Star newspapers shed light on the culture of corruption and inefficiency, excessive cost, poor planning, lack of competition, economic strain, delays, and questionable oversight.

While intended to boost trade capacity, its execution risks saddling Bangladesh with an overpriced, underperforming infrastructure burden. A drastic rethink—potentially halting for re-tendering or scaling down—seems warranted, though Jica’s influence may preclude such options. This “most expensive road” could symbolize waste rather than progress without rigorous cost control and transparency.

The Prothom Alo article focused on the 27.2-kilometre road linking the Matarbari deep seaport to Cox’s Bazar, costing Tk 129.42 billion (Tk 4.76 billion per kilometre), making it Bangladesh’s most expensive road. Key negatives included its exorbitant cost (236% higher than the Dhaka-Bhanga expressway), cost overruns from Tk 88.21 billion to Tk 129.42 billion, lack of competitive tendering due to Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica) loan conditions, a delayed timeline (2026 to 2029), and the financial burden of foreign debt.

Key Points from The Daily Star Report

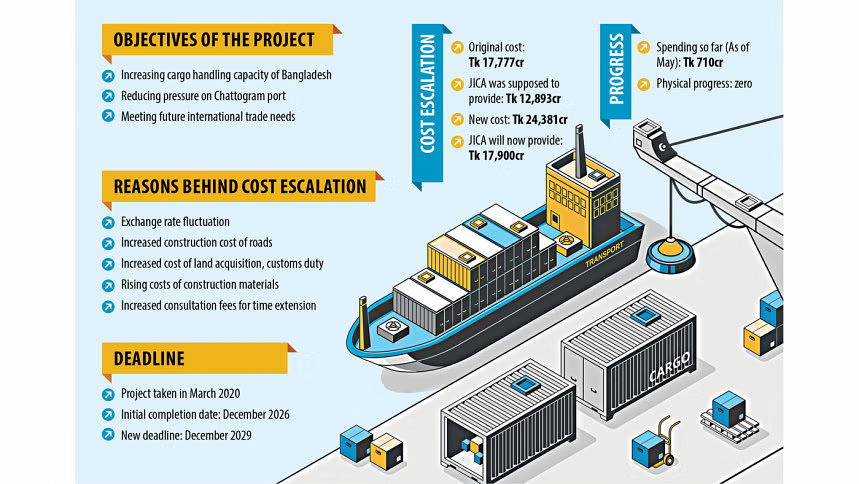

The Daily Star article addresses the broader Matarbari deep-sea port project, of which the road is a component. It notes:

-The total project cost has risen from Tk 177.77 billion

(March 2020) to Tk 243.81 billion after two revisions, a 37% increase, approved by the interim government in October 2024.

-The road component’s cost escalated from Tk 88.21 billion to Tk 129.42 billion, aligning with Prothom Alo’s figures.

-Reasons for cost increases include higher construction material prices (e.g., steel up 53%, cement up 19% since 2020), a 31% depreciation of the Bangladeshi Taka against the US dollar, and additional expenses like consultancy fees (Tk 15.47 billion) and a Tk 1 billion dredging contract amendment.

-Japan funds 80% of the project via a soft loan (0.7% interest, 40-year repayment), with Bangladesh covering the rest, but the rising costs strain local funding amidst a forex crisis (reserves at $13.9 billion usable, per Bangladesh Bank).

-Experts criticize the lack of competitive bidding and reliance on Japanese contractors, alongside poor initial cost estimation.

Unjustifiably High Costs and Escalation

Evidence: The road’s Tk 4.76 billion per kilometre (Prothom Alo) remains a standout concern, dwarfing the Dhaka-Bhanga expressway’s Tk 2.01 billion per kilometre. The broader project’s 37% cost hike (Daily Star) from Tk 177.77 billion to Tk 243.81 billion, with the road component alone jumping 47% (Tk 88.21 billion to Tk 129.42 billion), reflects systemic cost inflation.

Critical Take: The justifications—rising material costs (steel +53%, cement +19%) and currency depreciation (31% Taka drop)—don’t fully account for the road’s disproportionate expense compared to other national projects. The lack of detailed breakdown beyond soil conditions (Prothom Alo) and generic “risk assessments” by Japanese consultants suggests potential overengineering or padding.

Poor Initial Planning and Cost Estimation

Evidence: Both reports highlight repeated revisions—two for the road (Prothom Alo) and two for the entire project (Daily Star)—indicating flawed baseline estimates. The Daily Star notes an expert’s view that “initial cost estimation wasn’t done properly,” a sentiment echoed by the Prothom Alo assessment committee’s call for re-tendering.

Critical Take: This consistent underestimation undermines confidence in project management by the Roads and Highways Department (RHD) and Chittagong Port Authority. It suggests either incompetence or deliberate lowballing to secure approval, with taxpayers bearing the subsequent burden.

Lack of Competitive Tendering and Foreign Dependency

Evidence: Prothom Alo details Jica’s restriction to Japanese contractors, with bids (Tk 115 billion) exceeding estimates (Tk 73.82 billion) and Jica rejecting re-tendering. The Daily Star reinforces this, noting Japan’s 80% funding locks in Japanese firms, sidelining local or other international competition.

Critical Take: This monopolistic arrangement likely inflates costs, as evidenced by the 40% overrun post-negotiation (Prothom Alo). Experts in both reports (e.g., Shamsul Haque in Prothom Alo, Fahmida Khatun in Daily Star) argue that open bidding could reduce expenses, raising ethical concerns about prioritizing donor preferences over national interest.

Economic Burden Amid Forex Crisis

Evidence: The Daily Star ties the project’s rising costs to Bangladesh’s forex woes—usable reserves at $13.9 billion against a $12 billion debt repayment due in FY25-26. The road’s Tk 129.42 billion, part of the Tk 243.81 billion total, relies on a Jica loan (80%) and local funds (20%), straining an already depleted treasury.

Critical Take: Funding a luxury-priced road while seeking $5 billion from the IMF and World Bank (Daily Star context) is fiscally reckless. The 0.7% interest loan sounds favorable, but currency depreciation increases repayment costs in Taka, potentially deepening the debt trap.

Delayed Benefits and Questionable Returns

Evidence: The road’s completion has slipped from 2026 to 2029 (Prothom Alo), delaying its role in easing Chittagong port pressure and boosting cargo capacity (Daily Star). The broader port project’s timeline isn’t specified, but cost hikes suggest further delays.

Critical Take: With no clear cost-benefit analysis in either report, the project’s economic justification—handling 1 million TEUs annually (Daily Star)—feels speculative against its ballooning price tag. The delay risks rendering it obsolete or less competitive by completion, especially if global trade patterns shift.

Opaque Decision-Making and Oversight

Evidence: Jica’s veto of re-tendering (Prothom Alo) and the interim government’s approval of cost hikes (Daily Star, October 2024) amid political transition suggest rushed or unscrutinized decisions. Consultancy fees of Tk 15.47 billion (Daily Star) and a Tk 1 billion dredging amendment lack justification.

Critical Take: The opacity—exacerbated by reliance on foreign consultants and contractors—hints at potential mismanagement or influence peddling. The interim government’s involvement post-uprising adds a layer of instability, questioning accountability.

Critical Evaluation

The Matarbari road project, as part of the deep-sea port initiative, emerges as a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing prudence. The combined evidence from both reports paints a picture of:

-Financial Extravagance: A road costing Tk 4.76 billion per kilometre—far exceeding national benchmarks—coupled with a 37-47% project-wide cost surge, lacks credible justification beyond external factors like material prices and currency shifts.

-Systemic Flaws: Poor planning, restricted competition, and weak negotiation leverage (e.g., only Tk 2.67 billion shaved off) reflect a failure to prioritize Bangladesh’s interests over donor dictates.

-Economic Risk: In a forex-starved economy, this debt-funded megaproject diverts resources from urgent needs, with delayed returns amplifying the gamble.

-Governance Gaps: The opaque, foreign-driven process, approved amidst political upheaval, undermines public trust and long-term viability.

Leave a Reply